Isn’t it interesting that as we begin a new year on the Church calendar today, rather than talking about the beginning of time, we are talking about the end? Indeed, today’s liturgy – the collect, scripture lessons, hymns, and service music - tell us that we are by no means still in “Ordinary Time.”

The Collect of the Day for 1st Advent plunges us into the dichotomy between this mortal life and life immortal. It reminds us that at the moment of Christ’s second coming, whether we are living or dead, we will face his judgment. This is heavy stuff indeed, so much so that many - if not most - Christians choose side-step the second Advent - Christ’s Second Coming - and instead focus on the first Advent – Christ’s nativity. The nativity – with its emphasis on birth - indeed is much more comforting and joyful than death and final judgment. And many people have chosen the Episcopal Church precisely because they grew tired of their tradition focusing on things like judgment and hell. I would grow tired of a church that talked about that all the time too. But on the flip side, I have grown tired of churches that never speak of the things that make us uncomfortable. The Season of Advent offers a corrective to the theologically flimsy Moral Therapeutic Deism and Golden Rule Christianity that is so prevalent in many churches today. The Season of Advent boldly invites us to ponder our own mortality, as well as what will happen when Christ comes again. Only when we can come to grips with our own mortality will we be able to faithfully and authentically celebrate the meaning and consequence of the 1st and 2nd comings of Christ. So all of this being said…Happy New Year!

We must remember that during the High Middle Ages, death was an ever-present reality. Living conditions were wretched, and life expectancy was low, and the emergence of the Black Plague made things even worse. In those conditions, one couldn’t help but to have death on their minds. So Christians looked to the Church’s scriptures and tradition to help make sense of the awful reality in which they were living. After all, if the Church doesn’t have anything meaningful to say about this situation, what good is it?

The 1662 Book of Common Prayer included the following in the liturgy of the Daily Office: “Man, that is born of a woman, hath but a short time to live, and is full of misery. He cometh up, and is cut down, like a flower; he fleeth as it were a shadow, and never continueth in one stay. In the midst of life we are death.” While this might seem overly morbid to our post-modern ears, it was pastoral wisdom when it was written. When the plague hit London in 1665, indeed, these words were likely on the tip of every faithful Christian’s tongue. We may not have nearly as many health-related risks as folks did in the Middle Ages, but we still have biological limitations. No matter how advanced our society becomes, we will all die. And thus the Church is still called to give us the language, theology, framework, and community for dealing with death. Just as in generations past, if we can’t look to our faith tradition for wisdom and guidance as it pertains to death, to whom or what will we turn?

I think that one reason we as a society struggle to talk about death as openly as did those in generations past is that we have sanitized – and become sanitized to – the reality of death. The discovery of bacteria and infection, and the resulting emphasis on sanitation, was a landmark moment for humankind. Modern medicine, plumbing, vaccinations, and other medical progress has decreased infant mortality rates, increased life expectancy, and overall has lengthened and increased our quality of life. That is a very good thing. But a consequence of modern medicine and family structures is that we actually see death with our own eyes far less often. This is the first period of time in human history that people are more likely to die outside their own home – be it a hospital, nursing home, or Hospice Care facility. And when somebody dies, we don’t even like to say that they have died. The preferred figure of speech is to say that they have “passed away.” If you read obituaries in the paper, you’ll notice that we don't have funerals any more - we have Celebrations of Life. And the “celebration” that is being referred to is no longer the resurrection of Christ from the dead, and what that means for us when we die. The celebration simply begins and ends with the person whose life is being celebrated. If someone from generations past read a modern-day obituary of someone they knew, they might show up to the church expecting a birthday party rather than a funeral.

Thankfully, the funeral service in the Book of Common Prayer is called Burial of the Dead. And I hope that never changes. The service for the Burial of the Dead, in my opinion, is one of the most powerful, theologically rich services in the Prayer Book. It is simultaneously solemn and uplifting in a deeply reverent way. It doesn’t comfort us by evading or denying death. It provides comfort and solace by proclaiming what we believe to be true in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Perhaps another reason that we are so uncomfortable with death is that for many of us, life is relatively pretty good. But for those whose life here on earth is terribly difficult, death can be seen as a release from bondage. For slaves or other people living in abject poverty and oppression, death brought about a freedom that they never experienced in this life. But if our lives here are pretty good, death doesn’t seem like the better option. So do all that we can to extend our lives here on earth, and once death is imminent, we approach it like almost as if it were embarrassing inconvenience as opposed to natural a part of God’s created order.

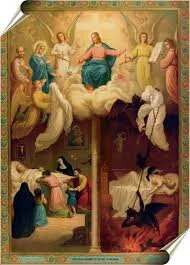

As such, while our ancestors spent much of their religious life focusing on preparing for a good, holy death, we tend not to do so. Of course, much of our religious life should be spent on how to live our lives here and now. But our scriptures and tradition call us to deal with the reality death as well. The Apostle Paul urges us to lay aside the works of darkness and put on the armor of light. And historically, Advent was the season that was set aside to ponder and prepare for these things. The four Sundays of Advent were set aside to meditate on what became to be known as the Four Last Things – Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell. The scripture lessons and collects during Advent still address these themes, but amazingly, we seem to skillfully find a way to avoid talking about them altogether.

The Advent wreath is an excellent example of how we have shifted our focus during the season Advent. Today, for most churches, the four exterior candles on the Advent wreath no longer represent the Four Last Things - Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell. They now are said to signify “Faith, Hope, Joy, and Peace.” Now don’t get me wrong – who doesn’t love faith, hope, joy, and peace? I certainly do. And when Emily and I gather around the table with Julian and Madeleine to light our Advent wreath, I’m much more comfortable saying, “This is the peace candle” than I am saying, “This is the hell candle.” I will likely defend my discomfort by saying that our children are too young to hear about things like death, judgment, and hell. But why? And what about adults? Why blame it on children? Why are we adults still so uncomfortable with these aspects of the human condition and Christian tradition?

The writers of The Living Church magazine remind us that the Four Last Things instill humility and acceptance of our limitations. We are not God, no matter how advanced we become with modern medicine and science. We will always be finite, mortal beings. And as such, we will all die. But we don’t have to die alone or in vain. Christ himself died, so that he – God incarnate - could fully experience the human condition, even death. But in Christ, death no longer has the last word. And Christ’s Body – the Church – gives us a community within which we are equipped to live a holy life and die and holy death. May we all live a holy, good life, and when it is time for us to die, may we all die a good, holy death.