When I arrived at church this past Friday morning, I went inside to turn on the lights and set out the bulletins. When I walked into the nave, I was taken aback by the sheer emptiness of the space. Thursday evening’s ritual of stripping the altar had done what it was supposed to do. It helped set the mood for Good Friday, so much so that I profoundly felt the absence of Christ in this space. There was no reserved sacrament in the aumbry. The sanctuary lamp had been extinguished. Christ was hauntingly absent from this place. Before the first word of the Good Friday liturgy was spoken, I had already felt the pang of Christ’s death on the cross.

For me this year, Good Friday did what it was supposed to do. I felt the power of Christ’s death in a way that I had never felt before. This palpable experience of death might also have to with the fact that we buried our beloved friend Tim Harbeson on the day prior to Good Friday. So, this week, death wasn’t just a symbol, or something for us to commemorate. The sting of death happened right here in our midst. And it hurt. The last prayer of the Good Friday service bids God to give mercy and grace to the living, and pardon and rest to the dead. As I read that prayer at the end of the Good Friday service, as well as at the end of the Stations of the Cross, it occurred to me just how much I long for and desperately need God’s mercy and grace while I am still living, as well as God’s pardon and rest when I die. Indeed, for me this year, Good Friday did what it was supposed to do.

And Easter Sunday is already doing what it is supposed to do. The haunting, bare emptiness of this space – the void I felt on Friday and Saturday – has been transformed. There is a power of presence in this place that was not here on Friday. I can hear it, see it, and smell it. In a few moments I will even be able to taste it when I eat the Body and Blood of Christ broken for me and for you.

I share my profound experience of Holy Week with you not to convince you of the efficacy of the Prayer Book liturgies for Holy Week…or to make you feel bad for missing the Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday services. I am sharing my experience of Holy Week with you because I believe that there was and is real power in Christ’s death and resurrection. And throughout the centuries the Church has done our best to communicate this power through our scriptures, hymns, liturgies, and traditions. These are important tools for us to employ as we seek to re-member – to put back together – the story of salvation history.

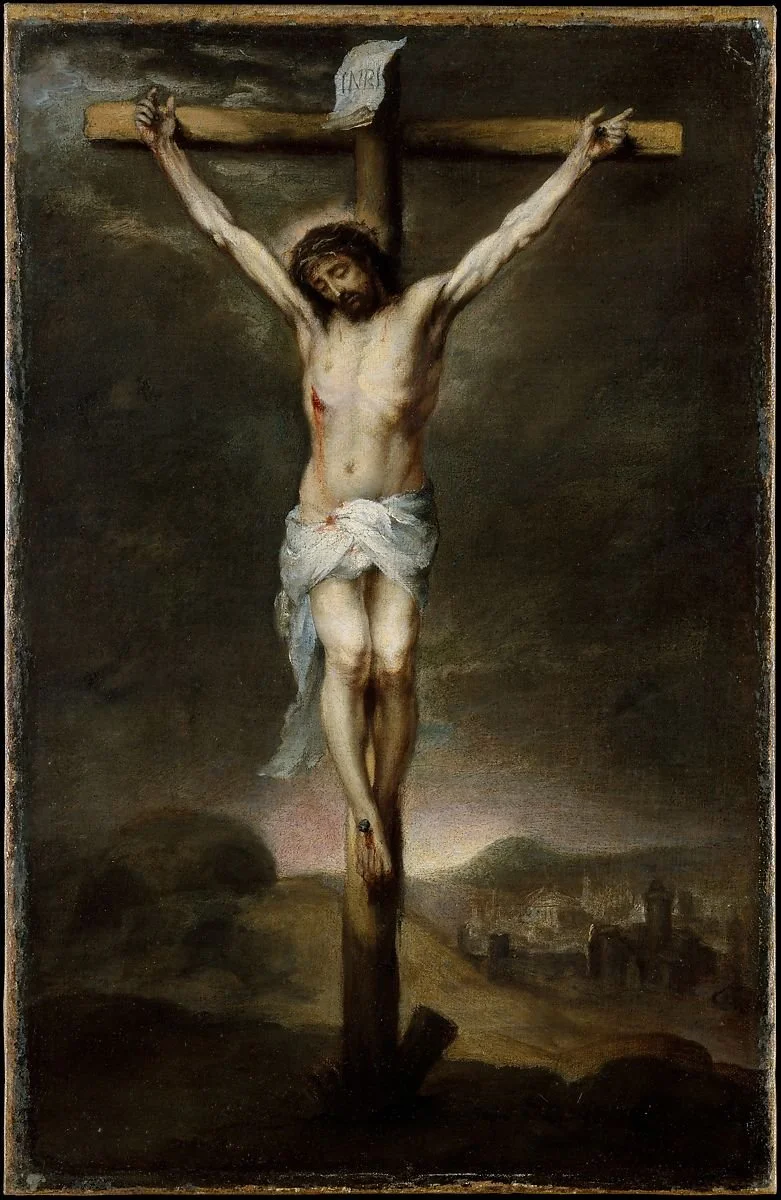

But we must be careful that in our attempt to faithfully tell and re-tell the stories of salvation history, we don’t fall into the trap of domesticating them. Christ’s death and resurrection were not private, religious events whose impact was only on those who were present. St. Matthew tells us that when Jesus died on the cross, “The earth shook and the rocks were split. The tombs also were opened, and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised…Now when the centurion and those with him, who were keeping watch over Jesus, saw the earthquake and what took place, they were terrified and said, “Truly this man was God’s Son!” Matthew is describing much more than a tragic death of a martyr. He is describing something much more than a religious, political, or historical event. He was describing a cosmic event – just like the resurrection, the death of Jesus was of cosmic significance. The entire world – past, present, and future – changed when Jesus died and rose from the dead. And the objective power of this fact doesn’t depend upon whether we believe it or not. But, if through the power of the Holy Spirit, we can come to truly believe in and experience the power of Christ’s death and resurrection, our lives will be changed forever – in this life and the next.

So, what does all this talk about the cosmic impact and proportions of the death and resurrection of Christ mean for us today? I think the power of the Christ’s death and resurrection lies in exactly that – power. The events of Holy Week – beginning with Jesus’ Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem a week ago, is all about power – namely, who has real power and who doesn’t. Those who derived their power from worldly, man-made sources– the Caesars and the Herods - tried to silence Jesus and then tried to silence his followers afterwards. They were terrified of his other-worldly power, as well as his ability to empower others.

When commenting on the power of the resurrection, NT Wright asks, “Who after all was it who did not want the dead to be raised? It was not simply the intellectually timid or the rationalists. It was, and is, those in power: the social and intellectual tyrants and bullies; the Caesars who would be threatened by a Lord of the world who had defeated death, the tyrant’s last weapon; the Herods who would be horrified at the postmortem validation of the king of the Jews.”

Holy Week reminds us of the power of God – Who is in control and Whose justice will reign. The powers and principalities of this world – both then and now - shake in their boots when the real source of power shows itself. We have seen this play out in the conflict between Ukraine and Russia. The Ukrainian people are drawing on a power that is much larger and deeper than the sort of power that Putin is trying to wield. And as the world is watching, praying, and helping the people of the Ukraine, we are becoming emboldened by a power that is not afraid of the bullets and bombs of a tyrant.

The power of God can be terrifying to those who resist it because its source is God himself. And God’s power cannot be contained by the Church or the state. This power is a cosmic power, not a worldly one. As Jesus said when he was being questioned by Pilate, “My kingdom is not from the world.”

As Christians, we are first and foremost an Easter people. Rather than resisting or being afraid of this power, we are called to submit to it, to embrace it, and to embody it. And that is when we will be able to fully participate in the work of God’s kingdom here on earth – God’s kingdom here and now, where

The wolf and the lamb shall feed together,

the lion shall eat straw like the ox…

They shall not hurt or destroy

on [the Lord’s] holy mountain.

As our collect for today says, we are called to “celebrate with joy the day of the Lord’s resurrection.” But this joy isn’t to be grounded in sentimentality. It is to be grounded in the cosmic, world-changing power of God who raised Jesus from the dead. And let us join with the psalmist in proclaiming,

"The right hand of the Lord has triumphed! *

the right hand of the Lord is exalted!

the right hand of the Lord has triumphed!"

This is the Lord's doing, *

and it is marvelous in our eyes.

On this day the Lord has acted; *

we will rejoice and be glad in it.”